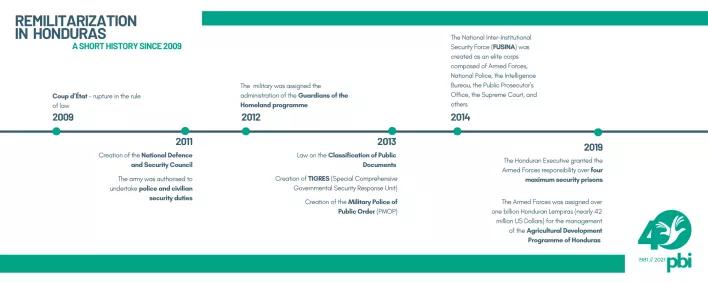

In late 2019, the Government of Honduras announced that the Armed Forces would be assigned over one billion Honduran Lempiras (nearly 42 million US Dollars) for the management of the Agricultural Development Programme of Honduras (PCM 52-2019), placing the programme outside of the mandate of the country’s agricultural institutions. The response from peasant organisations was swift: “The Government is paying off the military”, declared the National Centre for Field Workers (Central Nacional de Trabajadores del Campo – CNTC). The Centre’s Regional Office in La Paz explains that the same institutions that have harassed, attacked, tear gassed, and displaced them now wish to reach out to them as allies. “We are not going to accept that. We have accumulated a lot of distrust for them over the years”. For this reason, they add, they do not wish for “their genetically modified seeds to contaminate our lands”.

The remilitarisation of civil affairs is not a new phenomenon. The 2009 Coup d’État represented a rupture in the rule of law. In 2011, then-President of Congress and current President of Honduras, Juan Orlando Hernández, authorised the army to undertake police and civilian security duties through the creation of the National Defence and Security Council. This decree was enacted and published in the official journal on the same day, just five days after its approval. “This reflects an administrative efficiency that is very rarely seen from state institutions”, explains Fernando García, former Economic Minister. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights also denounced this situation in 2018, when it questioned the independence and impartiality of other state institutions.

The Creation of the PMOP, TIGRES and FUSINA

Another of the most significant events in the remilitarisation of Honduras was the authorisation of the military to undertake police functions “as a temporary measure” and in “emergency situations”, which was enacted through the Executive Decree on Security Emergencies (PCM-075-2011). This law, which has been extended on multiple occasions, attributes increased powers to the Armed Forces.

The creation of the Military Police of Public Order, commonly known as PMOP due to its initials in Spanish, followed this law, which also described the measure as temporary (Decreto 168-2013). Today, this body functions as the policing branch of the Armed Forces, with the objective of “maintaining and preserving public order, as well as aiding citizens to safeguard the safety of persons and property in cooperation with the National Police”. Beginning with 1,000 officers in Tegucigalpa and San Pedro Sula, by 2016 the PMOP had over six battalions of over 500 officers each. By 2017, there were over 5,000 officers. It is currently unknown whether any plan exists for their disbandment.

The special militarised police unit, TIGRES (Special Comprehensive Governmental Security Response Unit), was created in 2013 (Decree 103-2013). Trained by the US Green Berets, they are responsible for strengthening the State’s institutional actions in combatting insecurity. Although this unit forms part of the country’s police, its officers wear camouflage uniforms, carry long-range firearms, and have specialised communications equipment. Civil society organisations report that the TIGRES and PMOP perform hybrid security duties, such as patrolling streets and highways, maintaining order during public protests, and protecting mining and hydroelectric companies in cases of conflict with local communities.

One year later, in 2014, the National Inter-Institutional Security Force (FUSINA) was created as an elite corps composed of Armed Forces, National Police, the Intelligence Bureau, the Public Prosecutor’s Office, the Supreme Court, and others. With the objective of combatting organised crime, drug trafficking, and petty crime, FUSINA also maintains sub-groups to work in specific areas, such as the National Anti-Gang Force (FNAMP), created in 2018. There are a total of 19 different police and military units, each with responsibilities that can overlap with other units.

In 2018, in response to this situation, then-head of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) in Honduras, María Soledad Pazo,1 emphasised the need to demilitarise public security. “This is something we have been saying since our arrival. A Military Police that has not been trained for the tasks of a civil police force cannot be maintained, as the risks of human rights violations are high”. The Committee Against Torture similarly expressed their concern in 2016 over the normalisation of the militarisation of public security.2 These concerns are echoed in the annual reports of the National Human Rights Commissioner (CONADEH), which year after year contain reports of abuse, torture, arbitrary detention, break-ins, murder, and assassinations committed by these forces.

Entrance into Schools and Prisons

The remilitarisation of Honduras is not limited to citizen security; during this period, the Armed Forces have entered into other areas of civilian life. For example, in 2012 the military was assigned the administration of the Guardians of the Homeland programme, in which they entered into public schools to promote military, civic, and religious ideals. This was described by civil society organisations as “very disturbing”.

In late 2019, following the declaration of a State of Emergency in the country’s prison system due to the violent deaths of several inmates, the Honduran Executive granted the Armed Forces responsibility over four maximum security prisons. Although this was once again described as a temporary measure, the decision has not yet been reverted. Moreover, according to Migdonia Ayestas, coordinator of the National Violence Observatory of the National Autonomous University of Honduras (ONV–UNAH), their presence did not contribute to a decrease in human rights violations, as demonstrated by the eight violent deaths recorded in prisons so far in 2021.2 In light of this situation, the Board for Monitoring the Enforcement of the Sentences of the Inter-American Court warns that the militarisation of the prison system violates international human rights standards. Civil society organisations, such as ACI Participa, warn that this militarisation of the prison system, “will not lead to any change”, and although some intervention is necessary, “it must come from civil society”. The National Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Cruel and Degrading Treatment (CONAPREV), denounced that, “violent acts continue to occur in so-called maximum security centres, in which ungovernability reigns”. In these prisons, “military intervention has not been the correct response”, notes CONAPREV head, Glenda Ayala.

These new duties assumed by the armed forces have led to an increase in their budget. In 2020, the Defence Secretary’s budget was 344 million US dollars, an 8 million increase over 2019. Moreover, between 2016 and 2018, this budget increased by 7.2%, which, according to the OHCHR, “calls into question the commitment of the government to continuously advance civil security”. Similarly, the IACHR stated that, “history demonstrates that the intervention of armed forces in matters of internal security is accompanied by violations of human rights in violent contexts”. Furthermore, the OHCHR has observed with grave concern that the prevention of violence is a low priority issue, as it receives less than 6% of security budget funds. In this context, there are also many doubts over the manner in which the Armed Forces have managed these funds, as this information is a state secret, according to the Law on the Classification of Public Documents.

“Soldiers are intervening in matters of telecommunications, energy, justice… Moreover, we see that this militarisation seeks to entrench itself with a request to the next government for more funding for police and armed forces”, concludes lawyer and human rights activist, Reina Rivera.